Nearly 30 years after the establishment pitch count recommendations, I see more and more throwing injuries every year in my pediatric sports medicine practice.

Despite specific guidelines, including pitch counts and avoiding pitching with pain, young athletes continue to play, throw, pitch, and abuse their arm (or body) causing long-term and even disabling problems. This concern is not unique to baseball, as softball throwing injuries are also on the rise.

One player I met recently, “Sam,” is an avid Texas Rangers fan and loves baseball. When he was five, he began playing T-ball and within five years, he was on two teams and guest playing for a third travel team. Admired for his throwing form, mechanics, and accuracy, Sam played every chance he had. His parents explained that they know about pitch counts and other “rules” but found it hard to enforce since Sam loves baseball so much.

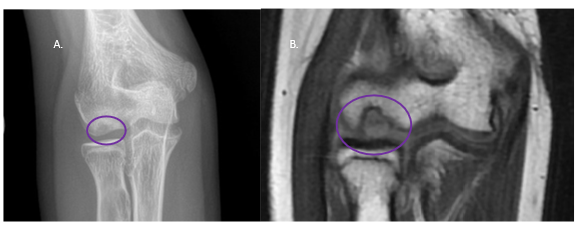

At 12, Sam began to complain of shoulder pain. A well-meaning coach suggested it was rotator cuff tendinitis, a condition that is not common in kids. When his shoulder pain transitioned to pain in the elbow, his parents took him for an evaluation. He had developed an elbow condition involving the bone and cartilage called osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the capitellum (an area in the elbow). Unfortunately, his condition progressed. Sam is now 14 and has daily elbow pain, significantly limited motion in his elbow, and is unable to play baseball. Sam also experiences pain and difficulty with everyday tasks like washing his hair and eating a hamburger.

You may think this story is extreme, but it is not unusual to see young athletes like this in my clinic. Overuse injuries from overtraining, lack of rest, and non-response to pain are common in baseball players. However, with the right information and action, I believe we can prevent these conditions. Together, we need to understand why this is happening, understand what the most common overuse injuries in youth throwers are, and learn how we can do better.

Why are throwing Injuries increasing despite injury prevention recommendations?

Professionally, I am a huge advocate for injury prevention in our youth. Through research and education, I work to understand why this is such a big problem. Then, I evaluate myself as a parent of two youth athletes and realize, in all honesty, I struggle to practice what I preach. In the book Playing to Win, Michael Lewis shares his experience as a parent in youth sports and describes that watching your kids play sports is like “watching the Super Bowl every weekend.”

You, me—we are the problem. It’s the parents that drive the $37.5 billion youth sports industry, now worth more than three times that of Major League Baseball. In recent conversations with a youth volleyball club owner and elite basketball coaches, I asked why they support year-round play, to which they answered that parents require and in fact demand it. They would all support proper rest if their businesses were not at risk of losing families to other clubs who provided more opportunities to play the sport.

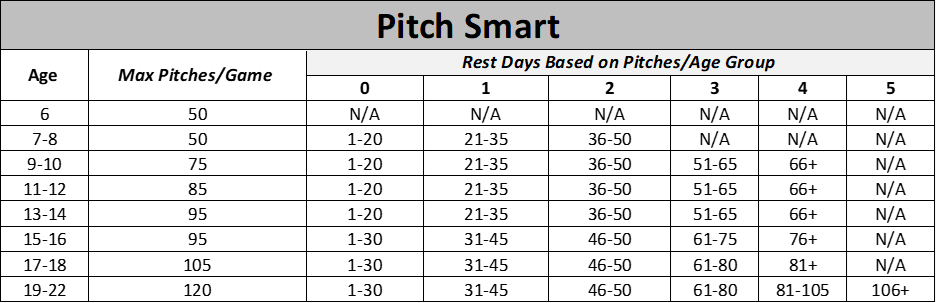

Rates of throwing injuries in youth continue to increase annually and compliance with safe throwing regulations is marginal at best, with only 58% of parents aware of pitch count.1,2 In 2014, Major League Baseball and U.S. Baseball developed a campaign called Pitch Smart that was updated in 2018 (Table 1). Although these guidelines are well-established, implementing them into practice is the responsibility of the player and parent, especially when playing for multiple teams.

What are common injuries from throwing?

Throwing Injuries in the Shoulder

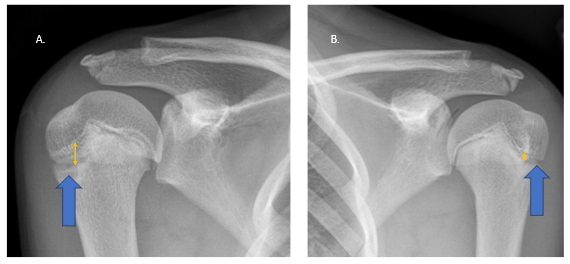

Little Leaguer’s Shoulder is a condition in which the growth plate of the upper arm (humerus) adjacent to of the shoulder endures too much stress with repetitive throwing. The growth plate sustains many tiny fractures that in time accumulate. Left untreated, the growth plate becomes inflamed, causes pain, and begins to break down. Athletes who take proper rest breaks during and between seasons allow these tiny fractures to heal and may never experience pain. When Little Leaguer’s Shoulder or humeral epiphyseolysis is diagnosed, the treatment is at least three months of rest from throwing and implementation of a progressive return to throwing program with a trained professional. If left untreated, Little Leaguer’s Shoulder may result in permanent changes to the shape of the bone, called retroversion. This may cause limited shoulder range of motion and pain with activities like throwing.

Shoulder injuries are also common in softball pitchers that utilize the windmill pitch style. These problems are typically more related to the bicep tendon or cartilage around the shoulder joint, called the labrum, instead of the growth plate.

Throwing Injuries in the Elbow

The elbow is a well-known area of concern with baseball throwers, particularly pitchers and catchers. Like the tiny fractures in Little Leaguer’s Shoulder, the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) has micro tearing that occurs with each throw. Over time, and without rest, the UCL will stretch out and cause pain that will lead to loss of strength when throwing. Tommy John, a professional baseball pitcher, was one of the first elite athletes to return to full activity after reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament. A study evaluating the concerning perception that this procedure may improve performance showed that 25% of parents do not believe that the need for Tommy John Surgery is related to pitch count. Further, 37% of parents believed that young healthy pitchers without elbow pain would benefit from Tommy John surgery.3 Despite many parents’ opinions, injury to the ulnar collateral ligament should not be taken lightly and more common once a young pitcher reaching skeletally maturity (around 15-16 years old).

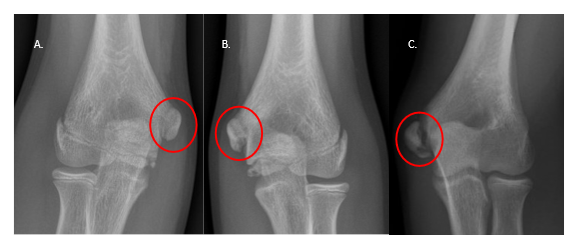

An ulnar collateral ligament injury in a young pitcher presents similarly to a more common condition called Little Leaguer’s Elbow or medial epicondylitis. Similar to Little Leaguer’s Shoulder, Little Leaguer’s Elbow is an overuse injury to the growth plate on the inside of the elbow. If neglected, Little Leaguer’s Elbow is likely to result in a fracture of the growth plate that may require surgery. When a thrower has elbow pain, especially on the inside of the elbow, an evaluation followed by rest for a minimum of three months is recommended to promote healing and avoid development of a fracture.

Other common elbow throwing problems include elbow impingement from bone spur formation, stress fractures and other ligament injuries. Another, less familiar condition, is called osteochondritis dissecans (or OCD). This is a bone and cartilage problem that becomes progressively worse without proper rest. OCD of the elbow typically occurs on the outside of the elbow in an area called the capitellum. Repetitive compression on the outside of the elbow from throwing can cause the bone underneath the cartilage to lose its blood supply. Continued throwing may also cause damage to the cartilage on the surface of the bone which can lead to arthritis in the elbow. Surgery is often required but is not always successful in returning the thrower to baseball.

How can parents, coaches and others help progress toward a better culture in youth baseball and softball?

As a parent, coach, or anyone related to youth sports including baseball, balancing health recommendations while promoting improved performance case be challenging. Rules such as playing in one league at a time, minimizing tournaments and showcases, limiting the use of a radar gun, and striving for proper mechanics are all important preventative measures. In addition, these three hard rules should always be followed:

- Never throw or pitch with pain. Clear medical evidence suggests that this leads to worsening problems in the elbow and shoulder.

- Monitor pitch counts. Parents or athletes should be responsible for pitch counts, especially for players who play for more than one team, because you cannot always rely on coaching staff.

- Take an off-season. All athletes need an off-season. Professional athletes take an off-season to rest their bodies. Youth athletes should too.

Globally, the only way to change the culture is to set an example as parents and coaches should always make decisions in the best interest of their youth players.

References

Eichinger JK, Goodloe JB, Lin JJ, et al. Pitch count adherence and injury assessment of youth baseball in South Carolina. J Orthop. 2020;21:62-68.

Lee A, Farooqi A, Abreu E, Talwar D, Maguire K. Trends in pediatric baseball and softball injuries presenting to emergency departments. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2023;51(3):247-253.

Tadlock JC, Eckhoff MD, Macias RA, et al. 2023. Journal of Surgical Orthopaedic Advances. 2023;32(01).